Seismologists study earthquakes by using a variety of methods to measure and compare them. The motion of the ground during earthquakes is recorded by instruments known as seismographs. The ground motion that people notice comes from a release of energy that radiates outward in all directions as seismic waves, which travel through the earth.

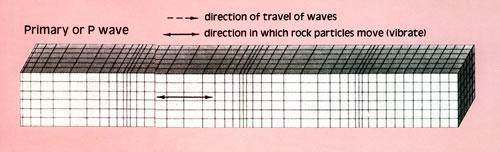

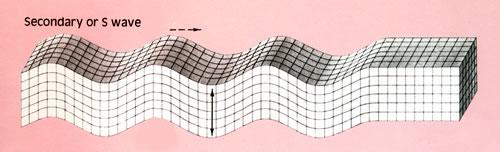

There are two basic types of seismic waves, body waves and surface waves. Generally, the first jolt felt during an earthquake is the push-pull body wave, or P wave, as it reaches the surface. A second jolt is another type of body wave, called an S wave.

At any given point on the surface of the earth, the motion we feel is the result of several kinds of seismic waves. The primary (P) and secondary (S) waves are body waves that radiate outward in all directions from the places where fractures are occurring.

The first motion you feel during an earthquake usually is a jolt from the P wave.

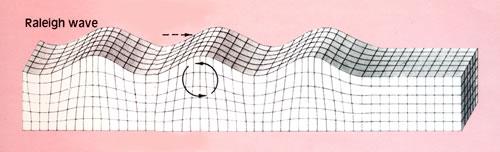

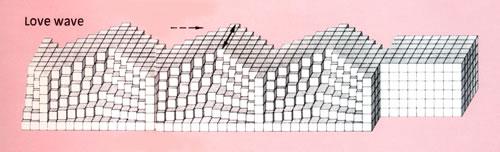

The rolling and swaying that follows body waves is caused by surface waves, which travel like waves of water. During a small earthquake, the earth’s movement along the fault line or fracture may be over in a few seconds. The motion felt during a major earthquake may last several minutes.

Seismic waves are sometimes of high enough frequency to be audible. Those who have experienced major earthquakes describe a noise that sounds like thunder, a distant locomotive, or a distant cannon-fire.

Most of the strain energy released in earthquakes is dissipated by breaking and crushing the rocks, by moving the adjoining blocks of the earth vertically and horizontally, and by creating heat.

Vibrations caused by earthquakes with epicenters in places as far away as China, Alaska, Iran, the Philippines and Mexico City have been picked up by a recording instrument in a water well in Rolla, Missouri, which is monitored by staff with the department’s Water Resources Center.

Seismograph stations are located throughout the seven-state region surrounding the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The majority of these are operated by St. Louis University, which began recording earthquakes in 1908. Today, nearly 50 university’s stations cover a six-state area. They record earthquakes in the New Madrid Seismic Zone and numerous earthquakes around the world.

Surface waves usually follow the P and S wave, traveling along the land surface like water waves. There are several types of surface waves; the two most important are Raleigh waves (R) and Love waves (L), named for the scientists who first identified them.

The R waves move continuously forward, although the individual particles move vertically in an elliptical path. This type of motion can be observed when a twig floats on a pond. If a stone is tossed into the water, the waves cause the twig to bob up and down, but the twig doesn't move forward in the direction of the waves because the individual water particles move only up and down. The L waves also travel forward, but the individual particles move back and forth horizontally.

On March 27, 1964, seismic waves from a major Alaskan earthquake were recorded on seismographs in the Midwest. The waves traveled almost 3,000 miles in slightly more than seven minutes. Water levels in Missouri wells rose and fell, and the water grew muddy. Some water levels fluctuated dramatically. Some returned to normal; others did not. Seismic seiches (singular, seiche; pronounced “saysh”) – or standing waves in rivers, reservoirs, ponds and lakes – were recorded at various places in Missouri. Fisherman at Table Rock Lake in Taney County noticed mysterious waves on the lake the night of the Alaskan quake.