Commodity

Lead is a soft, very dense, ductile, malleable, and corrosion-resistant metal. Lead currently is produced in Missouri from multiple mines in the southeastern part of the state, where it is found associated with zinc, copper and silver. Lead was named from the word “plumbum,” Latin for “liquid silver,” and which provided the source for lead’s chemical symbol of Pb.

The mineral galena (PbS), the official state mineral, is the primary ore for lead and has been mined for lead metal for more than 5,000 years. In Missouri, it has been mined for more than 300 years and had a strong influence on early settlement in the state. Early lead mining in Missouri also included the minerals cerussite (PbCO3) and anglesite (PbSO4), both of which are weathering products of galena.

Galena has also been a source for silver in southeast Missouri. While silver is not part of the chemical formula of galena, the silver atom fits in gaps in the crystal structure of galena, and was recovered when lead ore was smelted.

Economic Importance

Missouri has been a significant producer of lead throughout its history, including well before statehood; the first written record of lead mining by Europeans in Missouri dates to 1700. Continuous mining in southeast Missouri began in 1721. Lead mining was a major driver of settlement in the southeastern portion of the state, as well as a major influence on development in the southwestern portion. St. Francois County, which contains the Old Lead Belt subdistrict, quadrupled in population between 1870 and 1910 largely due to expansions in mining and mine-related milling and smelting. Early lead mining led to development and expansion of towns in both Madison and St. Francois counties. The last mine in the Old Lead Belt ceased production in 1972 as mining shifted to the Viburnum Trend, which produced its first ore in the 1960s and lead to major expansions in Missouri's lead production.

In the Tri-State District of southwestern Missouri, Native Americans and European hunters are said to have mined and smelted lead for shot at the site of the present town of Oronogo as early as 1836. The first major discovery was in 1851, leading to the establishment of mining camps, and development of numerous small mines. The town of Granby grew from sparsely populated open lands to a town of nearly 7,000 people, surrounded by 300 shafts, within a six-year span. While the Tri-State District is known for its zinc production, lead was the only metal recovered from early mining and dominated the district until 1872.

Missouri leads the U.S. in lead production (Guberman, 2017; Klochko, 2020) and has done so since 1907 (Kiilsgaard et al., 1967; Guberman, 2017; Klochko, 2020); until recently, the state was also a world leader in lead production. Total, all-time Missouri lead production is estimated at more than 30 million tons, valued at nearly $70 billion in 2018 prices.

Common Lead Ore Minerals in Missouri

Galena

- Chemical composition: PbS or lead sulfide. Galena that contains silver in the crystal matrix is known as argentiferous galena.

- Color and Luster: metallic lead gray, may tarnish to a dull dark gray or black.

- Hardness: 2.5.

- Cleavage: diagnostic perfect cubic cleavage, will cleave into shiny metallic gray cubes.

- Specific gravity: 7.6; due to the element lead, galena is noticeably heavy.

- Crystal habit: Often found as cubic crystals; modifications to octahedral shapes are also common.

- Named by Pliny the Elder from the Greek "galene" meaning "lead ore."

Cerussite

- Chemical composition: PbCO3, or lead carbonate

- Color and Luster: color varies from colorless to white, gray, blue or green. Luster varies from adamantine to vitreous, resinous, pearly, dull, or earthy.

- Hardness: 3-3.5.

- Cleavage: 2 distinct to good cleavages.

- Specific gravity: 6.5. Due to the lead, it is heavier than other carbonate minerals

- Crystal habit: Tabular to equant, dipyramidal. Often massive.

- Cerussite is from the Latin "cerussa," meaning "white lead."

Anglesite

- Chemical composition: PbSO4 or lead sulfate.

- Color and Luster: color varies from colorless to white, and is often tinted gray, yellow, green, or blue. Luster varies from adamantine to vitreous or resinous.

- Hardness: 2.5-3.

- Cleavage: 2 distinct to good cleavages.

- Specific gravity: 6.4

- Crystal habit: generally tabular crystals, sometimes massive.

- Anglesite is named for its type locality on the Island of Anglesey in Wales, United Kingdom.

Common Names

Galena is often described in historical records as "shine" or "shines" due to the shiny metallic nature of freshly broken pieces. It also is referred to as lead-glance, galenite, or, at times, simply "mineral" in historic mining records.

Cerussite and anglesite were frequently referred to as dry-bone in historic mining records as they were often white, massive, and earthy in texture.

Primary Uses

Lead-acid batteries currently account for 85% of U.S. lead consumption, and a major portion of Missouri lead production. It is a critical component for uninterruptable power sources for hospitals, computer and telecommunications networks, airports and utility infrastructure, with Missouri providing the high-quality lead required for these products. It is used in radiation shielding for medical applications, ammunition, electronics, protective coatings, glass and ceramics, specialty chemicals, machine components and as metal castings and sheet lead.

Past Uses

Early uses of lead included ceramic glazes, water pipes, roof metal, leaded glass and crystal, paints, burial vault liners, pewter, ammunition and protective coatings. Lead oxide was used as a wine-sweetener by the Romans. Lead was also used for printing press type, protective coatings, radiation shielding, solders and later for televisions and computer monitors screens. Lead was an additive in gasoline for decades.

Principal Locations of Lead in Missouri

Most lead mining occurred in several districts in the southern part of the state. The Southeast Missouri Lead District, Tri-State District and Washington County Barite-Lead District are all considered world-class mining districts. Significant to minor lead mineralization is found throughout large parts of Missouri.

Southeast Missouri Lead District

- Comprises several subdistricts: Viburnum Trend, Old Lead Belt and Mine LaMotte-Fredericktown.

- The Viburnum Trend (1955 to present) continues to produce lead along with zinc, copper, and silver. It also has the potential to produce cobalt. It is located in Crawford, Dent, Iron, Reynolds, Shannon and Washington counties.

- Mine LaMotte-Fredericktown (1720-1961), located in Madison and St. Francois counties, produced lead along with zinc, copper, cobalt and nickel. The Old Lead Belt (1700s to 1972), located in St. Francois County, also produced lesser quantities of zinc.

- The Southeast Missouri Lead District has ensured Missouri's position as the leading producer of lead in the U.S. for decades.

Tri-State District

- So-called as it covered portions of southwest Missouri, northeast Oklahoma and southeast Kansas.

- Tri-State produced zinc and lead in Missouri from the 1830s to 1957.

- Zinc and lead mining strongly influenced settlement and development of several areas of Missouri, most strongly in the southwestern counties of Jasper, Newton and Lawrence.

Washington County Barite-Lead District

- Historically an important producer and site of early lead mining in Missouri.

- Later lead production was as a byproduct of barite mining.

Several smaller districts also historically produced lead in Missouri. These are the Central Missouri District, where lead was produced with barite, and the Aurora District in Lawrence and Greene counties, where lead was produced with zinc. Smaller-scale lead mining also occurred in multiple other counties in southern Missouri.

Geologic Occurrence

Lead mineralization in Missouri is found in Mississippi Valley-type deposits; ore deposits with characteristic mineralization that formed in limestone and dolomite in specific geologic settings.

Lead-bearing ores such as galena and other minerals are primarily found in Cambrian- and Ordovician-age rocks in the Southeast Missouri Lead District and Washington County Barite-Lead District, Ordovician-age rocks in the Central District, and Mississippian-age rocks in the Tri-State District. Smaller mining areas in southern Missouri had lead ore hosted by Cambrian- through Mississippian-age rocks. Galena and other lead-bearing minerals are found as minor occurrences in most geologic age rocks in Missouri.

Throughout Missouri, ores typically are found in limestone and dolomite, and less commonly in sandstone. They also occur as residual ores in weathered ore-hosting rocks. In the Tri-State District, they also occur in jasperoid, a rock similar to chert. In all districts, ore minerals occur as crystals in open spaces and fractures or as fine grains of galena disseminated through and replacing the host rock. Disseminated ores comprise the majority of currently economic lead ores in Missouri.

Despite these similarities, there are also differences in the occurrence of lead ores in the different districts. In the Southeast Missouri Lead District, lead ores are generally disseminated or found as open space fill. They appear to have been concentrated by several mechanisms, including limestone-dolomite boundaries, solution-collapse breccias, faulting and fracturing of the host rock, pinchouts of overlying shales, and changes in host rocks related to buried Precambrian topography. An individual ore deposit will often exhibit several of these mechanisms acting in combination.

Mineralization in the Tri-State District is strongly controlled by folding and fracturing of the host rocks. Ores within Tri-State occurred in multiple forms, each with names well-ensconced in historic literature. "Circle" deposits are associated with sinkholes, and hosted the large, well-known surface mines of Oronogo Circle and Sucker Flats. "Runs" hosted the greatest quantities of ore and are linear bodies that follow fracturing or shear zones, often marked by extensive replacement of the host rock by silica or jasperoid. "Sheet ground" deposits have mineralization that followed bedding planes or other horizontal features of the rocks.

Mining

Early lead mining throughout the state was done on shallow or near surface ores, with limited shallow underground workings until the 1860s. Miners varied from full-time miners to farmers mining during off-months. Early mining was often of oxidized ores, as smelting was a simpler procedure for these minerals. During the 1860s, developments in drilling technology lead to deeper and more extensive underground mines, especially in southeast Missouri, although smaller hand and shallow underground mining continued into the mid-1900s. In addition, methods for processing the ore improved in the 1860s, allowing processing of greater quantities of ore and supporting larger mining operations. Improvements in groundwater pumping technology in the late 1800s lead to development of deeper, more extensive underground mines.

All current lead mining in Missouri is in the Viburnum Trend. Mining is entirely by underground methods and occurs at depths as great as 1,400 feet. Ores are blasted, crushed, transported to the surface, crushed further and run through flotation cells to separate the lead ore from the dolomite or limestone and other ore and non-ore minerals. Ores are then shipped to be smelted to generate lead metal.

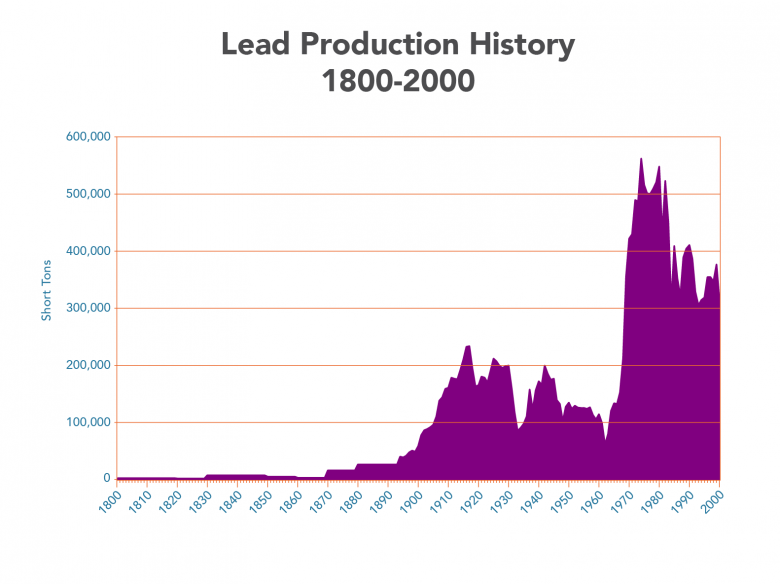

Production History

Lead production in Missouri from 1800-2000; production data for years later than 2000 are not available. Values for 1800 to 1893 are averaged from lump sums. The increase near 1970 marks increased production from the Viburnum Trend.

References and Additional Reading

Guberman, D.E., 2017, Lead; in 2015 Minerals Yearbook, U.S. Geological Survey, 17 p.

Kiilsgaard, T.H., Hayes, W.C., and Heyl, A.V., 1967, Lead and zinc; in Mineral and Water Resources of Missouri: Missouri Geological Survey and Water Resources, v. 43, 2nd series, p. 41–63.

Klochko, Kateryna, 2020, Lead; U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2 p.

Search the Missouri Geology Bibliography.

Visit the department’s Ed Clark Museum of Missouri Geology, where you will find lead samples on display.